Studies in Photography

News & Reviews

The Australian Question

By Sara Stevenson

Preamble

This article was first published in 1988, and requires some background explanation. The National Galleries of Scotland launched its formal interest in photography as an art form late in the day – in 1984. Julie Lawson and I were then faced with a distinct problem: how to build a collection of Scottish photography without sufficient and authoritative research on the subject – without even knowing who the significant photographers might be. With one or two exceptions, there was no ‘canon’. This was unusual and possibly unprecedented in gallery history – curators are supposed to have clear paths mapped out before them. So we needed to do two things simultaneously – to find the good pictures and to find the evidence on the makers; sometimes we could make these discoveries march together; generally we could not. It should be said that this pursuit was both a privilege and a pleasure, and, when we did line them up, we would have an exhibition and publish the information and pictures, so that we and the subject had ground to stand on for the next stage.

The following piece of research, which dates to this early exploration, was based on an unidentified group of calotypes of Australia and Peru already in the collection. We knew then, and this still holds true, that early photography, whether daguerreotype or calotype, was difficult, and the latter was especially erratic. From these early years there are remarkably few photographs remaining. The works of Talbot and Henneman and Hill and Adamson are the striking exceptions to this rule.

It stands to reason that very few people would successfully take photographs in the 1840s in Australia, which was distant from the sources of photographic materials, and was served by an incompetent merchant navy, in ships which were poorly built and sadly apt to sink (it is worth noting that the navy ship, described so disparagingly in this article, was far better built than most of the commercial ships). In 1848, an angry complaint was signed in the area of Australia, which is shown in the calotypes, Port Phillip, whose ‘Immigration and Anti-Shipwreck Society’ had held a public meeting. The Society was severely concerned about the loss of life and property in the wreck of ships heading their way, and both the damage and the discouragement to migrants[1].

In such circumstances, both the photographers themselves and their materials could easily have been lost to history, and the conditions of the return journey must have seen the destruction of yet more men and photographs. We are used to an idea of shipwreck relating to lost bullion or treasure; we should add the idea of lost daguerreotypes lying glinting on the sea bed and calotypes spreading and curling in the tide.

The survival of the group in the National Galleries collection is a matter of great significance and good fortune.

Footnotes

[1] W. M. Bell, ‘Report by a Committee of the Port Phillip Immigration and Anti-Shipwreck Society, Instituted in Melbourne, Port Phillip, at a public meeting held on 14th December, 1846’,The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle, vol 17, January 1848, p. 32.

The Australian Question

Or, Saved from the white ants and the happy cockroaches

Fifteen years ago, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery’s photography collection was divided into the world’s largest collection of calotypes by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson and several boxes, helpfully labelled ‘Miscellaneous’. The Hill and Adamson Collection demanded time and attention, and the other boxes were given only an occasional, slant-eyed, thought.

Sitting in these boxes was an odd group of seventeen calotypes – not particularly picturesque and not especially competent. But two were inscribed ‘Banksia, The Honeysuckle of Colonists’ (fig.13) and ‘Light Wood or Blackwood of Colonists. The wood resembled the Laburnum or Lignum Vitae’. From the authority of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the calotypes were assigned to Australia. From the time, any Australian interested in photography who passed through Edinburgh for her or himself looking at these photographs in confusions and fascination. [1]

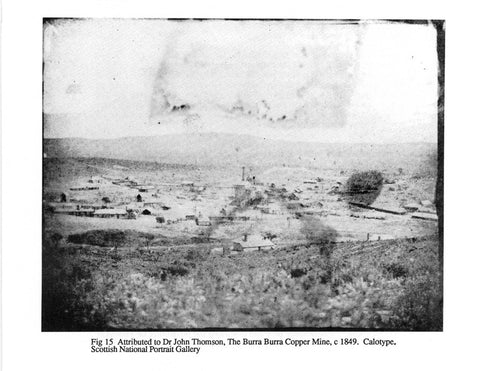

Christened by one Australian expert, Alan Davies, the ‘largest collection of Australian calotypes not eaten by the white ants’[2], they were eventually nailed down by another Australian expert through the calotypes of a mine (fig. 15). This proved to be the Burra Burra Copper Mine – a spectacularly successful mine, which attracted Cornish and Scots engineers – and the presence of a particular pump in the photograph dated the photographs to 1849.[3]

Logically, the photographer was a Scots mining engineer.

A second, smaller group of calotypes with similar annotations, looked South American. Recourse to the Encyclopaedia suggested Peru (Fig. 16).

After thirteen years’ acquaintance with these photographs, I was increasingly conscious that my research record was far from perfect. A hypothetical Scots engineer was not enough.

In 1985, there took place in Bradford a meeting of the European Society for the History of Photography which was particularly notable for bitter cold and rain which appeared to be driving at a 45 degree angle up from the pavement. Under the circumstances, the Scottish contingent tended to huddle together for warmth, and various right-minded foreigners, attracted by the kilowatts, the whisky, or the brilliance of the conversation, joined the Scottish Society for the History of Photography. Being responsible for giving a brief talk on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery’s collection to the conference, I decided to show a number of the photographs which had eluded our research. In a moment of aberration or good sense, it occurred to me to try out on the frozen, damp audience of considerable experts a method I cannot recommend to students on economic or moral grounds (more important, if you are a student – it takes too long). I put on the screen the Peruvian(?) photograph and offered a bottle of whisky for the correct answer. The answer came with exemplary speed from Hans Christian Adam that it was Peru and the city of Lima, which was, on his advice, later confirmed by the expert on Peruvian photography, Keith McElroy from New Mexico.

John Miller Grey, writing an introduction for Andrew Elliot’s book on Hill and Adamson in the late nineteenth century[4], talked about the 1840 Edinburgh Calotype Club and mentioned an album including calotypes of Peru: ‘One member (of the club) has penetrated to South America, and gives us renderings of the quays and public buildings of Lima’. This album is now missing[5], but the Edinburgh Calotype Club is known to have been an informal association of lawyers – men like Cosmo Innes and George Moir. The Burra Burra Mine was notable for its success and its enormous profits which involved the confusion and wealth attractive to the law.

The photographs were at this point, logically, likely to have been taken either by an engineer (with an encouraging side-bet on a guano miner) or a lawyer, and my colleague, Julie Lawson, followed the lines of research suggested by these theories – pursuing the careers of the Calotype Club lawyers and likely engineers. With no results.

In May of last year, a pleasing letter arrived from Elizabeth Edwards of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, a veteran of the Bradford conference. She enclosed a photocopy of a letter which she had found in Imperial College in London ‘whist looking for something else – having magpie instincts I had a photocopy made’. This letter was the key and the solution to the whole problem.

It was written by a Dr John Thomson of Rankeillor Street in Edinburgh[6] to Thomas Huxley, and was dated 1851. The letter reads:

‘My Dear Huxley

I was glad to hear that you had made short work of your Rheumatic attack. I remember very well how much a former attack interfered with your pleasure when in the bush in Australia…

I have been very busy with my Calotype and have arrived at a considerable proficiency. I have nearly discarded paper as the medium of receiving the negative picture and have adopted glass – two processes I follow and according to the intention I have in view. When I wish to take portraits I cover the face of the glass plate with collodion having in solution a few drops of Iodide of Silver dissolved in a saturated solution of Iodide of Potassium – the hydro of Carbon of Aether seems to play an important part in rendering the surface very sensitive after it has been dipped in a solution of Nitrate of Silver 30grs to [ ] 10 – 30 seconds give a good portrait in diffuse daylight. When my wish is to take scenery I find if the surface is not rendered very sensitive that the minute details of the landscape are more clearly developed. I therefore make use of albumen having mixed in it a little of a very strong solution of Iodide of Potassium to coat the surface of the glass – and when this covering is perfectly dry I dip the glass as formerly in to a solution of Nitrate of Silver 30 grs to [ ]. In both case the pictures are brought out by a mixture of Gallic and Acetic Acid and occasionally are not fully formed until after the lapse of two of three hours…’

At last we had an Edinburgh calotype photographer who had been in Australia.

This Dr John Thomson (fig.17) was a surgeon in the Royal Navy (inevitably neither an engineer nor a lawyer)[7]. He was connected with Thomas Huxley through a scientific survey expedition of the Australian Great Barrier Reef and the Torres Strait between 1846 and 1850. Dr John Thomson was the surgeon of the HMS Rattlesnake, the young Thomas Huxley was the assistant surgeon. Huxley viewed the ship with little affection: ‘Exploring vessels will be invariably found to be the slowest, clumsiest, and in every respect the most inconvenient shapes which wear the pennant. In accordance with the rule, such was the Rattlesnake, and to carry out of the spirit of the authorities more completely, she was turned out of Plymouth dockyard in such a disgraceful state of unfitness, that her lower deck was continually underwater during the voyage.’[8] While he had no affection for the ship, Huxley was fortunate enough to like the surgeon: ‘My immediate superior, Johnny Thomson, is a long-headed good fellow, without a morsel of humbling about him – man whom I thoroughly respect, both morally and intellectually, I think it will be my fault if we are not fast friends through the commission. One friend on board a ship is as much as anybody has a right to expect.’[9]

In a letter to his sister in October 1846, before the ship set sail, Huxley remarked ‘I have learned the calotype process for the express purpose of managing the calotype apparatus for which Captain Stanley [who was in charge of the expedition] has applied to the Government’[10]. It is, therefor, possible that the calotypes now in Edinburgh were taken by Huxley and given to Thomson, but he never mentions taking photographs in his diary of the expedition or in his letters home. The probability is that the senior officer took charge of the camera.

The notations on the calotype are compatible with Thomson’s handwriting in the 1851 letter, not with Huxley’s writing. The only references Huxley and his Australian fiancee, Miss Heathorn, make to photography refer to John Thomson. In 1850, Miss Heathorn’s diary recorded ‘heard that a Dr Thomson was taking a photographic likeness of Hal (i.e. Huxley) – how delightful to have a correct one’, which she followed later with a peeved note: ‘very indistinct – with the sailor’s cap’[11]. In 1851, when back in Britain, Huxley reacted to a more successful essay in portraiture: ‘Many thanks for the Calotypes – they are certainly as fine as any I have ever seen. Your own is especially sharp and life-like, and wonderfully like. As for your son’s, of course I can’t judge the likeness but I can quite believe it – as he has all that peculiarly sturdy, planted, look – a sort of jolly defiance to the world in general – which I have heard of as his characteristic. A most indubitable chip! – it makes me laugh whenever I look at him.’[12]

A later remark by Huxley suggests that photography was a sufficiently familiar topic between the two men to have become a mild standing joke. ‘Why don’t you exhibit some of your Calotypes [in the Great Exhibition of 1851]? It might do you good when you take to the peripatetic cart we used to talk about.’[13] Presumably they had discussed the possibility of Thomson setting himself up as a travelling photographer. A survey voyage was as uncomfortable an affair as Huxley’s description of the ship suggests. Men like Huxley with particular work to do, other than sailing the ship, and with their own cabins were exceptionally fortunate. The surgeon was kept intermittently active with epidemics – including one sinister enough to be worth writing up for a medical journal. Huxley urged Thomson to do so in 1851: ‘Do you ever intend to publish or make any use for yourself of the notes of our marvellous ‘Dopo’ epidemic? I mean that which began with the death of poor Taylor. I have mentioned the circumstances of that disease to several people of eminence… and they all strongly advise the publication of its details.’[14]

A four-year voyage when an epidemic becomes ‘marvellous’, required a man anxious to keep his sanity and his temper intact to think up a professional hobby and preferably one which would take him ashore. Huxley again described the condition of life on shipboard: ‘Any adventures ashore were mere oases, separated by whole deserts of the most wearisome ennui. For weeks, perhaps, those who were not fortunate enough to be living hard and getting fatigues every day in the boats were yawning away their existence in an atmosphere only comparable to that of an orchid house, a life in view of that of Mariana in the moated grange has its attractions.’[15] Huxley’s cynical view of life in the navy was published in 1854; (it can be safely assumed he was not expecting to take up a second naval appointment.) Huxley’s diary, which is unfortunately not a complete account of the voyage, records the surgeon’s absence in 1847 for some months and it is clear that the ships of the expedition went at times in different directions.

Regrettably the calotypes cannot be related directly to the account Huxley gave of the survey, and there must remain (temporarily, I hope!) a doubt of their being taken by John Thomson. The photographs of the mine are the only certainly identified pictures in the group and Thomson is not on record as having visited the mine, although it is surely probably that a general scientific survey would have sent representatives to look at such a spectacularly successful geological venture. There are however one or two more straws for brick-making that convince me he was the missing Australian calotypist. One photograph of a clapboard bungalow is inscribed ‘Talicum [? a place name] Geo Thomson’ [fig.18] – conceivably a relative of the photographer. John Thomson’s secondary interest in the expedition was the collecting of botanical specimens and the two properly identified photographs in the set are trees. Most important of all, he had the driving interest in photography necessary for this pioneer work.

Huxley’s friendship with John Thomson fives us a good description of this survey expedition. The known facts of his later life are less highly-coloured. The researches he described in his letter to Huxley in 1851 are mentioned in an article by William McCraw attacking another Edinburgh photographer, James Good Tunny, for claiming too much credit in his work on the collodion process. The article said ‘Perhaps it might be said that Mr Tunny is somewhat wanting in generosity in not acknowledging the invaluable serviced he was receiving from a gentleman, whose name I cannot mention without his sanction. This was Mr T., a doctor in the navy who was then enjoying some leisure time in the neighbourhood of Mr Tunny’s studio. The former gentleman devoted days and weeks together in experimenting with the latter, and many a message was sent from home for the errant doctor to come to his dinner.’[16] In much later years, when John Thomson had retired from the navy, he became the Vice-President of the Edinburgh Photographic Society.

Some doubt remains on the authorship of these particular Australian and Peruvian calotypes, but John Thomson certainly took calotypes during the Australian expedition and this fact alone entitles him to admiration. Anyone who has tried taking calotypes in comparatively rational conditions (during heavy rainfall in Edinburgh, for example) is familiar with the dim and incompetent results which are apt to emerge. Conditions on HMS Rattlesnake and the white ants between them make the taking and survival of these few early paper photographs astonishing – aesthetic criticism would be brutal and irrelevant. Within a few days of leaving Plymouth, the crew were so sick in the Bay of Biscay that they mostly lay in their hammocks oblivious of the water swilling around the cabins carrying their possessions with it. Some did not survive. John Thomson must have stayed on his feet and kept a careful eye on his calotype paper and chemicals, in intervals of tending the sick.

Huxley’s account of the later stages of the voyage is a yet more extraordinary description of conditions either for taking or for preserving photographs. In August 1849, he wrote ‘I wonder if it impossible for the mind of a man to conceive of anything more degradingly offensive than the condition of us 150 men shut up in this wooden box, and being watered with hot water… . It rains so hard that we have caught seven tons of hot water in one day… the lower and main decks are utterly unventilated: a sort of solution of man in steam fills them from end to end, and surrounds the lights with a lurid halo… my sole amusement consists in watching the cockroaches, which are in a state of intense excitement and happiness…’[17]

Dr Thomson’s photographs survived the huger of the white ants and the damp affection of happy cockroaches – that in itself justifies at least one small firework in the Bicentennial celebrations.

Footnotes

[1] So many people have been involved in this subject in the last 15 years that I can, to my shame, no longer remember precisely who said what about these calotypes. My gratitude and apologies are offered to the unsung heroes of this dubious exercise in scholarship.

[2] The Australians, who do everything on a more enthusiastic scale than the British, (having more room), have white ants where we might have clothes moths – the difference being that white ants will eat spades. Information from Alan Davies, lunch, 1986.

[3] For the Burra Burra mine, see Ian Auhl and Denis Marfleet, Australia’s Earliest Mining Era, 1975.

[4] J M Gray in the introduction to Calotypes by D.O. Hill and R. Adamson, 1928, pp3-4

[5] Another album is in the Edinburgh Central Library.

[6] Ms letter, Huxley Papers, 27.328, Imperial College, London.

[7] Dr John Thomson graduated as a surgeon in 1832 and died in 1891 or 92. This is not the John Thomson who visited China and produced the Street Life in London photographs, nor the John Thomson who was a partner of James Ross.

[8] The Life and Letters of Thomas Huxley, ed. Leonard Huxley, 1903, p.47.

[9] Ibid, p.46

[10] Ibid, p.39

[11] Appendix to T H Huxley’s Diary of the Voyage of HMS Rattlesnake, ed. Julian Huxley, 1935, p.305

[12] Ibid, p.361

[13] Ibid, p.365

[14] Ibid, p.360

[15] The Life and Letters, p.71

[16] William McCraw, ‘The True Origins of the Collodion Process in Scotland’, The British Journal of Photography, 17 December 1869

[17] The Life and Letters, p.72

Postscript

But this is now 2020. And, after this disconcertingly long period of time, it is clear that I was wrong in my conclusion in 1988. Dr John Thomson was a photographer, who operated in Australia at the time. But he was not the man who took this particular group of pictures.

Research is not a straightforward or linear process – and those of us who have found ourselves watching Hercules Poirot more than is sensible lately, (as a defense against viewing programmes about deep-cleaning the house), will recognise his method. Assemble everyone in the library and accuse everyone in turn until the correct suspect is pounced upon. And everyone is amazed…

So. We need to return to the Edinburgh Calotype Club and reconsider the members.

In 2002, an album of photographs taken by members of the Club turned up at auction in the south of England, and the National Library of Scotland were successful in bidding for it. Amongst these is a calotype, which is a second copy of one in the Portrait Gallery group and is identified as ‘Kitchen hut, Gnarkeet Station, Port Phillip, Australia’. The photograph is initialed ‘R.T.’ From meticulous research by Roddy Simpson, which is available online at the National Library’s site, the story was unlocked. Roddy gives us his biography:

Robert Tennent (1813-1890). In volume 1, the photographs initialled ‘T’ refer to ‘H. and R. Tennent’. Born in Edinburgh in 1813, he was the elder son of Patrick Tennent (1782-1872), Writer to the Signet, and Margaret Rodger Lyon (1794-1867). He was the brother of another member of the Edinburgh Calotype Club, Hugh Lyon Tennent. Robert was one of a number of family members who sailed around the Western Isles in July 1838. An account of this cruise is held at the National Library of Scotland, (shelfmark Acc.12071). Robert Tennent arrived in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) in June 1839 from Leith and crossed to Port Phillip in October 1839. Along with Charles Hugh Lyon (1825-1905), he held a squatting run of nearly 30,000 acres at Gnarkeet, 100 miles west of Melbourne from 1844 to 1853. Tennent also held 75,000 acres in the Portland Bay district, 20 miles from Gnarkeet, from 1841 to 1848. He married Wilhelmina Meldrum in 1858 at Kincaple, Fife and in his will he left property in Melbourne to his daughters. [1]

Sheriff Hugh Lyon Tennent was known to be a member of the Edinburgh Calotype Club, but his brother had previously been unknown to photographic history. His absence in Australia makes this reasonable. It now seems likely that the group in the Gallery’s hands is the remainder of a collection similar to the albums, and had belonged to Sheriff Tennent or his brother.

Robert Tennent operated under remarkable difficulties in a hot, dry climate – the cool moisture of Scotland was a definite advantage to photographers. It is especially pleasing that ‘The Kitchen hut’ is annotated as having been taken with a camera constructed out of a cigar box and the lens of a telescope. Allowing that a cigar box was probably a much finer object in the 1840s than it may be now, it was still an achievement. Tennent’s splendid amateurism is a cliché of early photography, and I do not know of any other successful pictures remaining which were indeed taken by this implausible, pioneer method. The other calotypes are evidently taken with, at the least, a better lens. [2]

It is pleasing also to be able to report here that a group of 19 negatives and positives has surfaced, given by Thomson’s son to the Oxford Museum of the History of Science. Though so far, none of these seems to have been taken on the voyage.

It should, however, be added that we have never identified the photographer of the calotypes of Peru with confidence. And that reminds me, that, shamefully, I never organised the bottle of whisky to be sent to Hans Christian Adam – a debt I should honour when it proves to be practical!

Footnotes

[1] https://digital.nls.uk/pencilsoflight

[2] Fortunately, we were able to publish the correct version of the story in Sara Stevenson and A.D. Morrison-Low, Scottish Photography: the First Thirty Years, National Museums Scotland, 2015, p.321.